In India, travel has always been noisy, colourful, and intense. For decades, it meant movement, between states, languages, cuisines, and climates. But something quieter is beginning to take shape within this chaos. Travel in India is slowly becoming less about where you go and more about how you live while you are there.

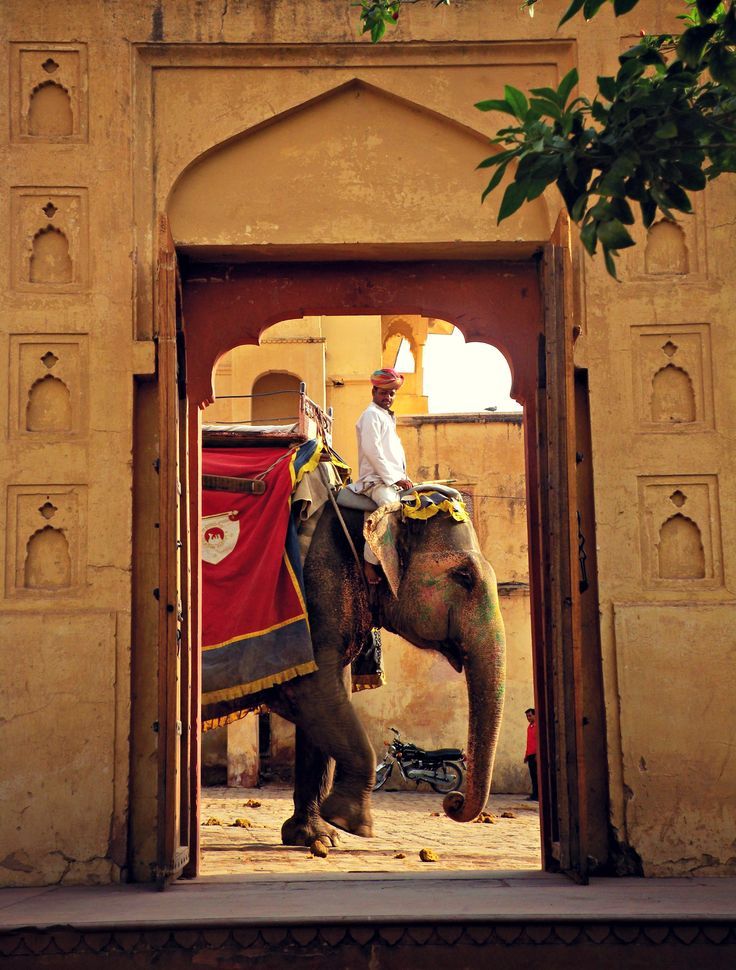

This shift shows up most clearly in how people choose to stay. Instead of hotels designed to feel neutral and temporary, travellers are increasingly choosing spaces that already belong to someone. A spare room in a Himachali home. A tiled house in a Tamil town where the mornings begin before sunrise. A courtyard in Rajasthan where the day revolves around shade and silence. These places come with routines, expectations, and an unspoken invitation to adapt.

Borrowed living in India is deeply shaped by rhythm. You learn when the water comes. When the power cuts. When the kitchen is active and when it rests. Meals arrive on time, not on demand. Tea appears without asking. Conversations unfold slowly, often without urgency. This is not curated hospitality. It is everyday life, briefly shared.

What makes this kind of travel different is how ordinary it feels. There are no monuments demanding attention, no pressure to document. Instead, meaning settles into smaller moments, sitting through an afternoon nap time, accompanying someone to the local sabzi market, listening to the evening aarti without fully understanding its words. These moments would never make it into a guidebook, yet they define the experience.

In Indian homestays and small-town rentals, travellers often find themselves absorbing habits unconsciously. Eating earlier. Sleeping earlier. Walking more. Speaking less. Life begins to organise itself around daylight, weather, and community rather than schedules and notifications. This borrowed structure often feels grounding, especially for those coming from crowded cities where time feels constantly borrowed by something else.

This form of travel also carries a quiet humility. India does not adjust itself easily to visitors. Travellers adapt to shared spaces, different hygiene standards, unfamiliar food, and a pace that cannot be rushed. There is learning in this adjustment. You realise how deeply lifestyle is shaped by place, climate, and history.

Borrowed living in India also creates unexpected emotional connections. You stop being “the guest” and start being “the person staying upstairs” or “the one who drinks tea without sugar.” Recognition replaces novelty. Belonging, even temporary, becomes the real souvenir.

This way of travelling is especially appealing to people seeking something softer. Not escape, not thrill, not spiritual transformation, just the chance to exist differently for a while. It offers relief from performance-driven travel, where every moment must be photographed or justified.

When travellers leave these spaces, they rarely describe the trip in terms of highlights. They talk about mornings. About the sound of pressure cookers. About shared silences. About how time felt heavier and slower, in a good way.

Borrowed lives do not promise transformation. They offer perspective. They show that within India’s vastness are countless ways to live a day, organize a household, and define comfort. And once you have lived inside another rhythm, even briefly, your own life never returns quite unchanged.

For More News updates : https://asiapedia.in