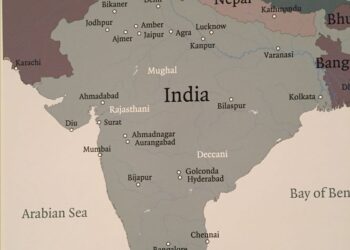

In India, travel has always followed water long before it followed roads.

Look closely at a map, not the political one, but the lived one, and you’ll see that journeys still bend around rivers, tanks, canals, and wells. Highways may dominate modern imagination, but water quietly continues to decide where people stop, settle, worship, and move next.

This is not poetic nostalgia. It is infrastructure logic.

Across the subcontinent, entire travel rhythms depend on water availability. Pilgrimage towns rise along riverbanks not only for spiritual reasons, but because rivers historically made long-distance movement possible. Even today, buses pause near river crossings longer than scheduled. Markets thicken near ghats. Temporary settlements form where water is accessible.

Stepwells in Gujarat and Rajasthan were never just architectural wonders; they were a travelling infrastructure. Designed as resting points, social spaces, and survival stops, they allowed caravans and travellers to move through arid regions without permanent settlement. Travel didn’t avoid harsh landscapes; it learned how to pause within them.

In modern India, this relationship hasn’t disappeared; it has adapted.

Water tankers now function as moving lifelines in cities and tourist regions alike. In hill stations, beach towns, and pilgrimage centres, the arrival of tankers dictates hotel occupancy more than tourist demand. A place may be “open” for visitors, but without water, movement halts quietly.

Canals continue to shape travel routes in agricultural belts. Roads often mirror canal lines, not by accident, but because human movement follows irrigation logic. Where water flows, labour follows. Where labour gathers, transport adapts.

Even urban travel bends to water systems. In cities like Chennai or Bengaluru, monsoon floods reroute daily movement, redefining which areas are reachable and which disappear temporarily. Travel becomes seasonal not because of tourism calendars, but because drainage systems decide accessibility.

River ferries, often ignored in mainstream travel narratives, remain essential connectors. They shorten journeys dramatically, bypassing long road detours. For locals, these are not experiences; they are efficiency. For travellers, they reveal an older geography still very much alive.

Tourism, too, relies on water more than it admits. Resorts cluster near lakes and rivers. Festivals align with water cycles. Travel seasons rise and fall with groundwater levels, not just weather forecasts.

What’s striking is how quietly this system operates. There are no signboards announcing water dependency. No guidebooks explaining why a place feels suddenly “unavailable.” Yet water governs movement with firm invisibility.

Understanding India through water changes how you travel. You stop seeing destinations as fixed points and start seeing them as conditional, dependent on flow, storage, and access. You realize that journeys here are not linear; they ripple outward from water sources.

India does not merely travel over land. It travels through water, remembering ancient routes even as it builds new ones.

And once you notice this, the map never looks the same again.